I’m a consumer. You’re a consumer. We’re all consumers. We hear the word so often we don’t think about it any more. What is a consumer? People who go shopping? People who buy electricity or gas? People who put petrol or diesel into their vehicle – we’re all consumers. Being a consumer is a good thing. We hear about how The High Street is returning to normal. People are buying again. Consumers are driving the economic recovery. Prosperous times are ahead.

But what does it really mean to be a consumer? The dictionary definition is:

verb: to consume

1.

eat, drink, or ingest (food or drink).

(of a fire) completely destroy.

use up energy or resource

2.

buy (goods or services).

“accounting provides measures of the economic goods and services consumed”

3.

(of a feeling) completely fill the mind of (someone).

It is explicit within the definition that once the thing being considered is consumed, it is gone – it has been used up. It cannot be used again. This is obvious when we consider food, gas, electricity, water etc. We buy them, we use them up, we need to buy more.

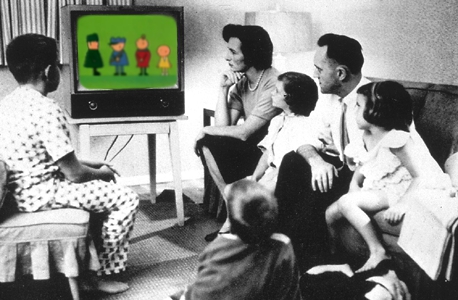

But when we consider ‘consumer goods’ the connection doesn’t seem as obvious. Think of consumer goods, and we think of TVs, microwaves, mobile phones, fridges, handbags, clothing etc. Anything you can buy on the high street. But we don’t consume televisions. Do we?

I read in a newspaper article recently about the built-in disposability of all consumer items. It investigated how consumer goods are deliberately manufactured with a limited lifespan, to encourage people to dispose of their products sooner than they otherwise would do, so that they buy new ones to replace them.

Take gadgets: We are made to feel inferior if we are using a phone/tablet/etc that is outdated. The latest model has a faster processor – better screen – more features. “You’re not still using an iphone four are you?” I know most decent folk would not actually voice such thoughts, but they still think them. Even though the phone still does everything it did when you bought it, perfectly, it’s no good any more. Its lifespan is dictated by a relentless and increasingly rapid product obsolesence cycle.

When I was little, black and white TVs were still around, and colour TVs were becoming commonplace, and getting our first colour TV seemed a straightforward (although incredibly exciting) affair. In the early 1980s, one didn’t need to consider whether or not it was HD, LED, TFT, plasma – you just bought the biggest box you could afford, and stuck it in the corner of the room. If you were flash, you got one with a remote control. And it stayed there until it broke.

But now television manufacturers are trying to drive sales by employing the same obsolesence cycle used for mobile phones. Are you still watching HD? That’s so last year – got to go 4K darling, so much better. Then there’s 3D; curved screens; Dolby Surround – only 5.1? Really? Get with the times, 7.1, dear.

It seems to me that everything is being turned into something we can consume. I’ve been a computer gamer since the invention of the species in the 1980s (ZX Spectrum rubber key vintage) and what got me thinking about this whole issue was the shift in computer gaming over recent years.

Before DVDs, one used to buy a computer game on a CD or floppy disk(s) (or if you’re ancient like me, cassette tape!) You bought the disk, you installed the game on your computer, and you played it. You played it as much as you liked, as long as you liked (or until mum or dad sent you to bed). All the features of the game were there right from the start, unlocked and ready to play, and you never had to pay another penny.

Compare that to today, where the model of financing computer games has shifted to a licensing agreement. Next time you buy a computer game, read the small print in the EULA (End User Licence Agreement) – all of it, I dare you. You will be surprised. When you hand over a few crisp notes or a credit card for that latest game at your local high street retailer, you’re not buying a computer game any more. You’re paying for a licence to play it. The disk is incidental. It’s just given to you as a means by which to exercise that licence. In fact, you don’t even need disks any more. Major game releases are increasingly being supplied online by game management systems like steam and origin. Saves a fortune on pressing, printing and labelling.

Of course, as all modern gamers know, the latest development in computer game financial models is that the games are being given away free of charge. The software companies make their money by online micro payments from within the game itself. You want a super-zap wizard spell? That’ll be £0.69. Cast it, and it’s gone. Oh dear – the ogre’s not dead. You need another one? That’ll be another £0.69.

Before, the most anyone paid for a computer game was the price on the label. Now, there is no limit to how much someone can spend on one game. Cha-ching. The game has been completely consumerised. A good thing for the software companies, no doubt. Not so much you and me.