The Reading workshop time capsule recreating one of the world’s first electronic computers

A home workshop in Reading is today playing a vital role in the reconstruction of EDSAC, the Cambridge University machine that 65 years ago led the world’s computing revolution and today is being reconstructed and assembled at The National Museum of Computing on Bletchley Park where the process can be watched by Museum visitors.

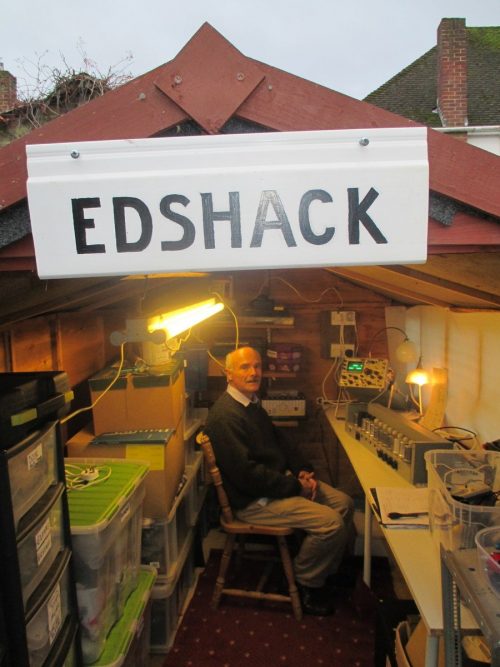

The Reading workshop, affectionately named Edshack, belongs to James Barr, who not only has the rare skills required to help in the reconstruction of EDSAC, but also has a computing pedigree that can be traced directly to the machine that first ran before he was even born.

EDSAC was built in Cambridge in the years following the Second World War and was the first high-speed electronic computer ever to go into service at a University. Because of its remarkable speed, it enabled new approaches to scientific research, which were previously impossible, and was used in at least two Nobel-Prize winning research breakthroughs.

In Barr’s workshop, key components of EDSAC’s central control system are being reconstructed. He is one of the very few people in the country who could attempt such a task. It requires a knowledge of thermionic valves that were used for war-time RADAR and preceded the invention of transistors and silicon chips. They were the only devices at that time fast enough for a high-speed computing technology. He also has had to research and re-discover the ways that 1940’s valve circuits were made to perform digital functions.

James Barr’s pedigree in computing owes a remarkable debt to the 1949 EDSAC computer. He recalls: “I left Newton Abbott Grammar School, Devon, in 1972, and went up to Downing College, Cambridge University. Computer Science was a fledgling science at the time and only after first studying ‘proper’ science for two years was it permitted to take computer science as a subject in its own right.

“That computer science course was run by none other than Sir Maurice Wilkes, computer pioneer and designer of EDSAC. The other course lecturers were a remarkable team of famous computer pioneers. I still have my detailed notes and coursework that are proving to be a rare archive, giving insights into the development of early computing and its education.”

After Cambridge, Barr went on to work in the computer industry as a programmer and then project manager and analyst. He has witnessed first-hand the remarkable growth of one of the world’s fastest-growing industries from the 1970s until his retirement at the end of 2012. It was then that he was amazed to hear of the reconstruction of EDSAC and felt he might have something to contribute.

Andrew Herbert, leader of the EDSAC reconstruction project, said: “Edshack is one of several home workshops across England that are being transported back in time as they play their part in the reconstruction of EDSAC, one of the world’s earliest computers. Reconstructing a computer using technologies that are 65 years old might seem impossible, but we are fortunate in having a window of time in which to utilise the skills of people like James who have an understanding of a range of technologies from thermionic valves through transistors to silicon chips. Of course, we need to be careful not to get ahead of ourselves and to be faithful to the technologies that actually existed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, so that the EDSAC we recreate is as close as we can possibly get to the original machine.”

Today, the ongoing reconstruction of EDSAC is a favourite amongst Museum visitors and provides an outstanding artefact to teach aspiring engineers and computer scientists on the Museum’s Learning programme about the development of computing, a phenomenon of our age.

To find out more about the EDSAC Project, see www.edsac.org and short videos telling the story of the reconstruction at http://www.tnmoc.org/special-projects/edsac/project-videos.